Advocate that state agencies develop a streamlined process that facilitates rapid response upon detection.

Successful rapid response will require close coordination with regulatory agencies and a willingness on the part of regulators to streamline permitting processes, where feasible. Laws and permitting, specifically with respect to application of herbicides, need to provide a path to rapid treatment of new infestations. Existing permitting processes in many states have review and public notification timeframes that hamper the ability to treat hydrilla quickly. Thus, there is a need for a streamlined permitting process. Such a “rapid response” permit should be considered by state agencies for treatments of areas under 3 acres to provide leeway for managers to quickly address new infestations.

Eradication is a multi-year effort and requires a long-term commitment. Since successful eradication programs often require more than five years of treatment, it is important to obtain support from agencies and project proponents, as well as a sustained funding source.

Herbicide application is the most effective means of hydrilla management in the Great Lakes. Grass carp, which have been implemented at a much lower frequency in small water bodies, are used in concert with herbicides to manage lower-level infestations. The U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center is currently researching potential biocontrol agents for monoecious hydrilla, but no such agents are currently available. Mechanical controls are not a preferred management option unless the infestation is limited to a small patch of hydrilla that can be isolated with a curtain. Mechanical controls can be costly, labor-intensive, and result in extensive spread of plant fragments.

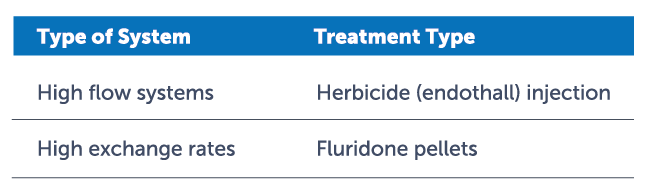

Hydrilla can be found in a variety of systems, from lakes and reservoirs to flowing streams. Identification of the most effective treatment plan for each site is a case-by-case exercise. The following is general guidance:

Refer to the Case Studies page for examples of management in various systems.